Artists and The Public

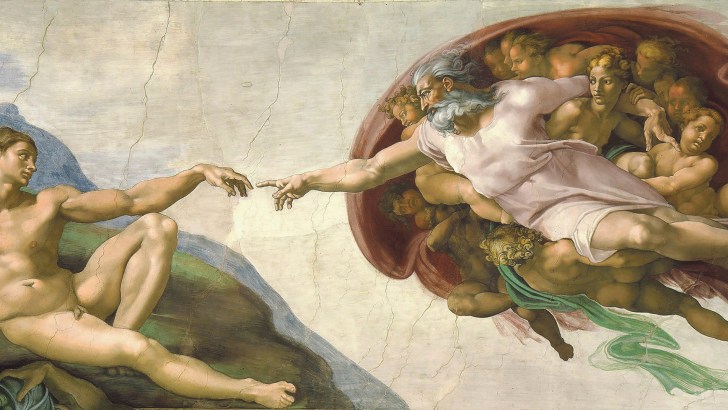

I was re-reading Ernst Gombrich’s excellent “The Story of Art” recently and came across a fascinating and very insightful section on early 19th century painting. Gombrich refers to this period as ‘Permanent Revolution’ and describes the impact of artists exhibiting and selling their work directly to the public for the first time rather than being commissioned by patrons and also the shift to teaching in academies from traditional pupillage.

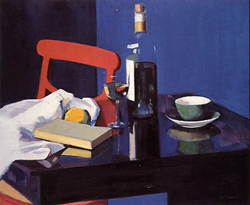

“The life of an artist had never been without its troubles and anxieties, but there was one thing to be said for ‘the good old days’ – no artist need ask himself why he had come into the world at all. There were always altar paintings to be done, portraits to be painted; people wanted to buy pictures for their best parlours, or commissioned murals for their villas… He delivered the goods which the patron expected…It was just this feeling of security that artists lost in the nineteenth century. The break in tradition had thrown open to them an unlimited field of choice. It was for them to decide whether they wanted to paint landscapes or dramatic scenes from the past…but the greater the range of choice had become, the less likely was it that the artist’s taste would coincide with that of the public. Now that this unity of tradition had disappeared, the artist’s relations with his patron were only too often strained.”

“The patron’s taste was fixed in one way: the artist did not feel it in him to satisfy that demand. If he was forced to do so for want of money, he felt he was making ‘concessions’, and lost his self-respect and the esteem of others. If he decided to follow only his inner voice, and to reject any commission which he could not reconcile with his idea of art, he was in danger of starvation. Thus a deep cleavage developed in the nineteenth century between those artists whose temperament or convictions allowed them to follow conventions and to satisfy the public’s demand, and those who gloried in their self-chosen isolation.”

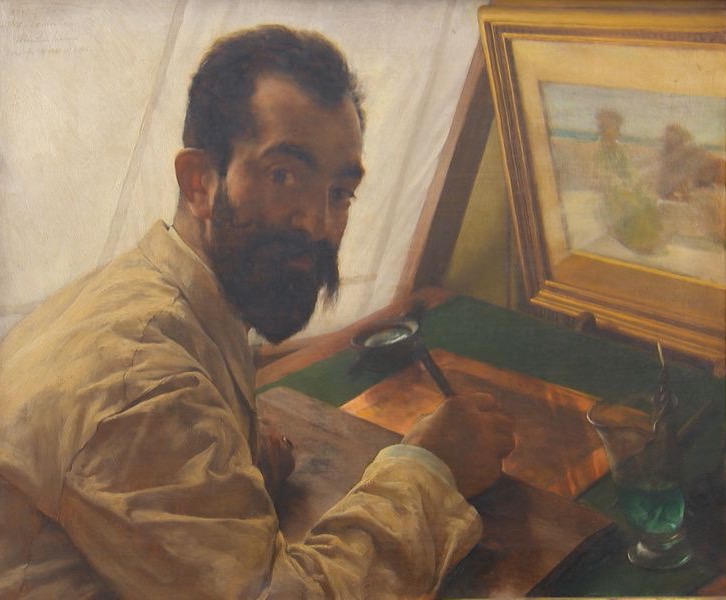

“The distrust between artists and the public was generally mutual. To the successful businessman, an artist was little better than an imposter who demanded ridiculous prices for something that could hardly be called honest work. Among the artists on the other hand, it became an acknowledged pastime to ‘shock the bourgeois’ out of his complacency and to leave him bewildered and bemused. Artists began to see themselves as a race apart, they grew long hair and beards, they dressed in velvet or corduroy, wore broad-brimmed hats and loose ties, and generally stressed their contempt for the conventions of the ‘respectable’.”

“The artist who sold his soul and pandered to the taste of those who lacked taste was lost. So was the artist who dramatized the situation, who thought of himself as a genius for no other reason than that he found no buyers…For the first time, perhaps, it became true that art was a perfect means of expressing individuality – provided the artist had an individuality to express.”

And that’s pretty much where we remain – some 200 years later….

If you don’t want to miss out on further blogs then please follow me on johngooldstewart.com