Glasgow Central Station

We are fortunate in Britain to not only have had so many fine Victorian railway stations, but also that so many have survived the onslaught of 1960’s and 70’s comprehensive redevelopment. In Glasgow, Buchanan Street Station is now a distant memory, we have lost St Enoch along with its magnificent hotel, but Queen Street survives (recently transformed by BDP while retaining its elegant glass roof) and the best of the lot – one of the country’s greatest stations – is Glasgow Central, which still serves over 30 million passengers a year from its 17 platforms and magnificent concourse.

The original station on the site was opened in 1879 by the Caledonian Railway Company to take trains north of the Clyde and directly into the city centre for the first time. In 1883 Rowand Anderson added his elegant Central Hotel with its great (somehow rather Scandinavian) tower but by the turn of the century the original eight platforms could no longer cope either with the daily commuters or the growing numbers of summer holidaymakers.

The Caledonian’s Chief Engineer Donald Matheson led the redevelopment of the station and engaged his old school friend and former Caledonian colleague, architect James Miller, to work with him. The scale of their redevelopment of the station was quite astonishing, starting with a new bridge over the Clyde which continued over Argyle Street to carry the additional lines into the expanded station itself. This now occupied an entire city block with Miller providing an extension to Anderson’s hotel and glazed screen to the Argyle Street bridge on the west side, and a massive new seven storey, twelve bay office block, Caledonian Chambers, to enclose the platforms and concourse on the east. Within, innovative elliptical arched girders on rivetted steel columns carried the station’s glazed roof (which was reputed to be the largest of its type in the world on its completion).

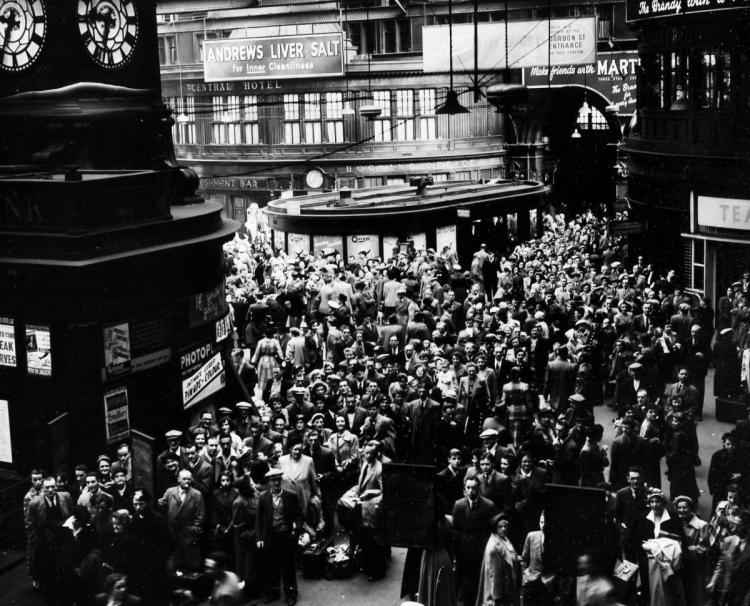

What lifts Central Station above the norm however is the vast sloping concourse over which crowds of passengers flow down to the exits on Gordon Street and out into the city beyond. Matheson had travelled to the States and witnessed the use of curved rather than rectilinear buildings to ease the movement of crowds noting “the tendency of a stream of people to spread out like flowing water and travel along the line of least resistance.” Miller immediately grasped the principle and provided all his kiosks, tea rooms, ticket offices and extensions to the hotel in a series of sinuously curved elements which contrasted with the insistent rhythm of the grid of the steel roof structure above. This brilliant urban space, designed entirely for human movement, has been the scene of many, often emotional, departures and arrivals over the last century, with Simon Jenkins even going so far as to suggest that it has become the “custodian of the city’s soul”.

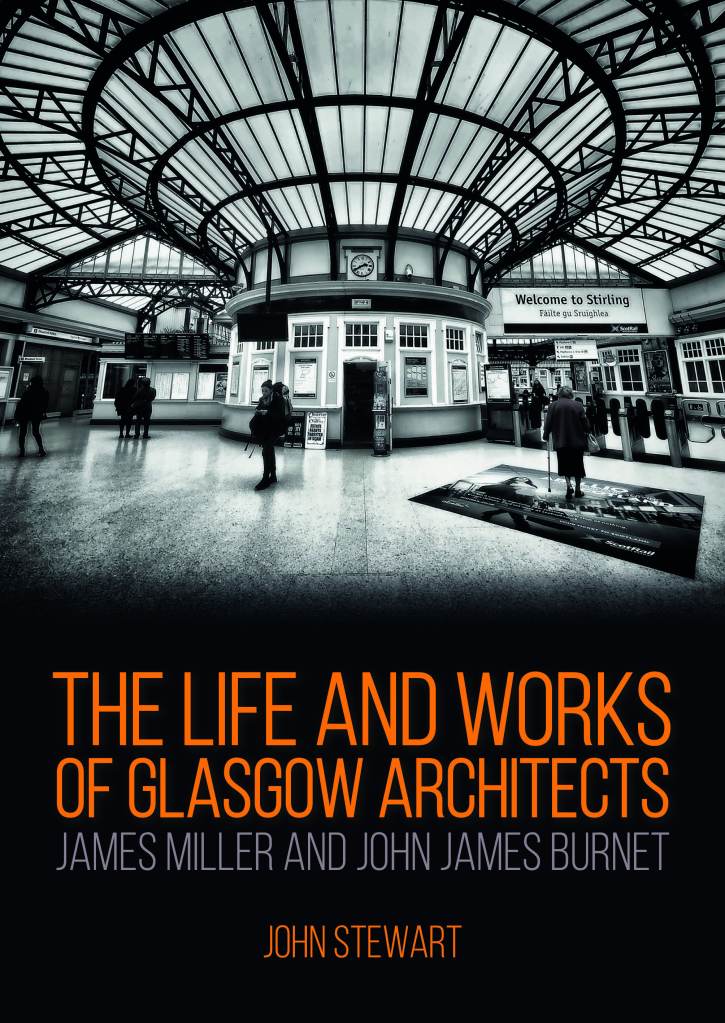

My book on the lives and work of James Miller and JJ Burnet will be published by Whittles in September this year. If you don’t want to miss out on further blogs then please follow me on johngooldstewart.com