Stormont

You probably recognise this building as a backdrop to various news reports on Northern Irish politics and it was here that the 700 hours of negotiations to secure the Good Friday Agreement took place. Its official name is ‘The Parliament Buildings’ of Northern Ireland, reflecting the original plan to have two separate office and parliament buildings, but as is so often the case with public projects – the money ran out and both functions were combined into one new building, by relatively little-known architect Arnold Thornely (1870-1953). Architecturally, perhaps what’s most surprising about it is that it was commissioned in the early 1920’s and officially opened in 1932.

It certainly bears the stamp of imperial authority but this has much less to do with imposing Great Britain’s will upon the disputed province of Northern Ireland and much more to do with the final doomed attempt to sustain the British empire by creating largely self-governing dominions who having been given greater autonomy, it was hoped, would remain as loyal constituent parts of the empire. This building thus has to be read as part of a vast imperial building programme which was carried out across the globe in the first part of the twentieth century.

It is an Irish cousin to Herbert Baker’s Indian Parliament House in New Delhi (above 1921-27), his Union Buildings in South Africa (1909-13), John Campbell’s New Zealand Parliament House (1914-22) and John Smith Murdoch’s Old Parliament House in Canberra (1914-27) and was required following Dublin’s adoption as the capital of the independent Irish Free State in 1921. In Northern Ireland, the Stormont Estate on the edge of Belfast was purchased to provide a prominent site of sufficient size, high above the city, whose rising ground offered what was perceived as the perfect setting for a new parliament building.

Thornely’s design originally envisaged a central dome, which would echo that of Belfast’s magnificent City Hall, but this too became the subject of cost-cutting, leaving just its mighty base, which was then, rather successfully (though unpatriotically), given a certain Germanic flavour with more than a hint of Schinkel. Otherwise, though very finely executed, it is all pretty straightforward stuff – two parliament chambers at right angles either side of the main central axis – all as ‘the mother of parliaments’ in what was then ‘the mother country’. The interiors are good with just a hint of what was then contemporary Art Deco.

Comparisons with its colonial cousins are interesting – New Zealand and Australia are similar classical blocks, India, as a result of the Indian Princes demanding their own distinct space, has three chambers, contained within the great colonnaded ring proposed by Lutyens, while Baker’s Union Building in Pretoria offers a much richer interpretation of the type (albeit minus the parliament chamber, which for political reasons, was located in Cape Town). Baker offered twin towers (as at Wren’s Greenwich), representing the two races – Boers and British (no – not black and white) who now jointly ruled the new South Africa. These enclose an external amphitheatre as a symbol of transparent government and the whole series of terraces upon which the complex is sited cascade down – not to a formal axial drive – but into a public park, which fortunately still remains open to the public, though it is now dominated by a statue of Nelson Mandela.

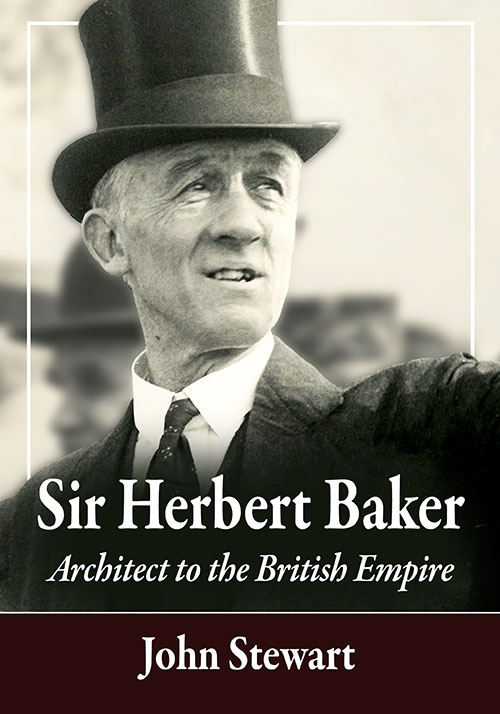

My biography of Herbert Baker is due for publication this autumn. If you don’t want to miss out on further blogs then please follow me on johngooldstewart.com