Edwin Lutyens

Any discussion as to the greatest 20th century British architect must now include the brilliant Edwin Lutyens. His reputation has risen from the ashes of complete contempt in the decades after WW2 to being widely regarded as a title contender. His best work is now well known but his rather extraordinary career is less well understood.

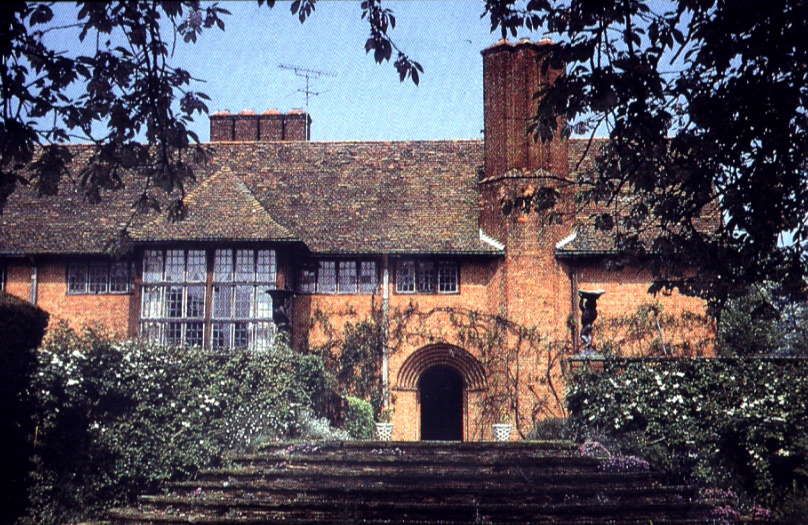

Like a number of other great architects, he started his own practice with little or no practical experience and in Lutyens’ case, without even a formal architectural education, having spent only two years at South Kensington School of Art and 18 months in the office of Ernest George. In 1889 at the tender age of 19, he was commissioned to design Crooksbury (which was to be a holiday home for Arthur Chapman who had known Lutyens since his childhood) and so he left George’s office and set up shop in his parent’s house in Onslow Square in London. Within a few years, an introduction to Gertrude Jekyll the famed garden designer provided him with a further client (her Munstead Wood of 1894-5 being the finest of his early works) an older and wiser muse, and of course, introductions to her own clients and her circle of wealthy acquaintances.

During the following, quite astonishing, ten years, Lutyens established himself as the leading designer of country houses in England and by 1905 had completed Deanery Garden, Tigbourne Court, Homewood, Little Thakeham, Nashdom, Greywalls, and the magnificent Marshcourt, as well as numerous further less well-known houses – but here lay his problem – he was now regarded as an architect who specialised exclusively in large country houses for the wealthy and as the years went by, he became more and more convinced that if he was ever to be mentioned in the same breath as Inigo Jones or Christopher Wren, he must attract public commissions.

In 1907 he spent 9 months working on his competition entry for the London County Council buildings, but was utterly devastated to lose and shocked by both the expense of the exercise and his considerable loss of income. In 1908, he discussed a partnership with Herbert Baker, who had already completed numerous commercial, ecclesiastic and public buildings in South Africa, but Baker decided to remain there for a few years longer. In 1910 his wife, a leading theosophist, managed to steer the new headquarters building for the Theosophical Society in London his way, but it proved to be a disaster with him so exceeding the budget that construction was abandoned with only a shell completed.

The turning point was his appointment as a member of the Delhi Planning Commission in 1912 (for which he and his wife Emily – a former Viceroy’s daughter – had to pull every possible string) and his subsequent appointment to design the Viceroy’s House the following year. Though this too was fraught with financial crises, it allowed him to finally undertake a major public building. His design of The Cenotaph in 1919 brought him public acclaim and was followed throughout the 1920’s and 30’s by a string of banks and headquarters buildings, before what would have been his greatest achievement –Liverpool Roman Catholic Cathedral – on which construction was halted by WW2 (by which time its estimated cost was running at three times its budget with only the crypt complete). By the time of his death in 1944 he was generally regarded as Britain’s leading architect, was a knight of the realm, an RIBA Gold Medallist and President of the Royal Academy and it’s highly unlikely that he’d have reached these heights had he not finally broken out of his early type-casting.

If you don’t want to miss out on further blogs then please follow me on johngooldstewart.com