Frank LLoyd Wright

If there is such a thing as an architectural genius – someone who appears to simply have an innate ability to produce outstanding original art – then Frank Lloyd Wright surely qualifies. From a relatively conventional architectural education and apprenticeship there emerged a revolutionary young architect who completely rethought the meaning of The House in the twentieth century. Wright literally exploded its traditional concept of enclosure and replaced it with a new model of horizontal planes floating around a vertical solid fixed anchoring point in space, in the form of a fire and massive chimney.

His early Prairie Houses also somehow managed to encapsulate the American Dream – free from all the constricting traditions of old, tired Europe – a land of endless possibilities, equal opportunities, natural beauty and vast spaces and yet – there were a remarkable number of architectural traditions which he maintained in contrast to the later heroes of Modernism such as Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rhoe. For example, he maintained the primeval concept of the family gathered around an open fire as the very centrepiece of all his houses (even later symbolically, in California, where fires would rarely have been lit). While most of his compositions were asymmetrical and responded to their site and surroundings, he also used symmetry as an ordering device in a way which became entirely unacceptable within mainstream Modernism.

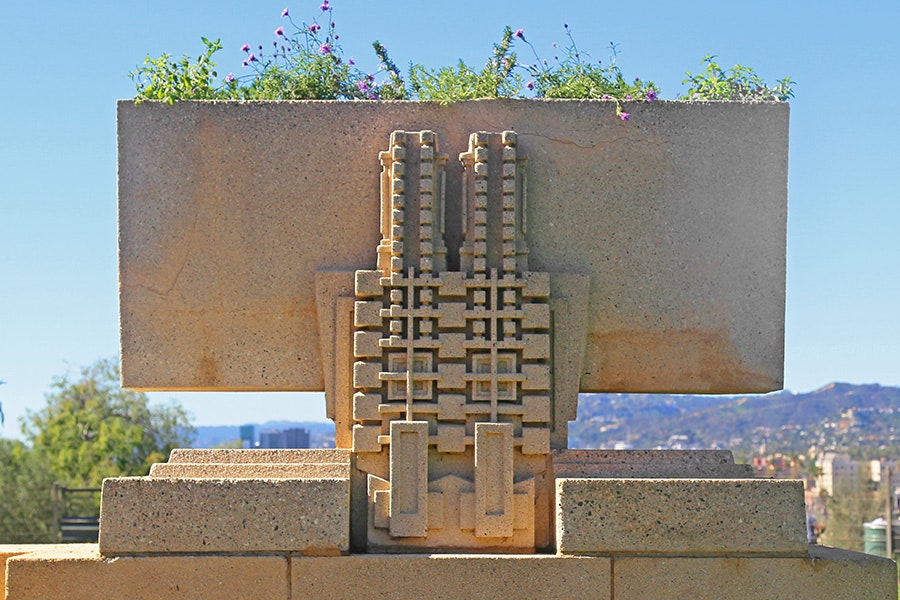

Far from rejecting traditional materials, Wright’s extraordinary imagination and creativity allowed him to recast them in entirely new ways and while he often adopted (and occasionally developed) the latest technology, he was also quite at ease providing the dramatic ‘Fallingwater’ with traditional slate floors or adopting the local Oya stone for complex carving in his Imperial Hotel in Japan. Differentiating himself even further from the mainstream, he also revelled in committing that greatest of Modernist sins – providing rich architectural decoration – in wood, stone, concrete and stained glass and while many of his spatial concepts were radical and much admired by later architects, the sheer creativity of Wright’s work at this level was quite extraordinary, almost entirely unique, and is generally quietly ignored.

I’d suggest that while his (by all accounts) vast ego allowed him to fearlessly reimagine almost every problem or opportunity that he was presented with, it was his focus on providing spaces that supported, celebrated and enriched the simple timeless human activities that make up our lives, that produced works of architecture that have now become as popular amongst architects as they are with almost everyone else who has discovered them.

If you don’t want to miss out on further blogs then please follow me on johngooldstewart.com