Beaux Arts architecture and planning suggests a very formal and rather sumptuous form of classicism in which grand axes and monumental buildings combine to create magnificent civic spaces. The Mall in Washington DC is a prime example, along with Hausmann’s Paris and Imperial New Delhi. The style was developed in the 19th century at the impressively named École Nationale Supériuere des Beaux Arts in Paris. At that time, Paris was the undisputed capital of the art world and the École was the world’s leading school of architecture.

Its origins lay in the Academie Royale d’Architecture, which was established in 1671 during the reign of Louis XIV with the aim of assuring the highest level of taste for royal buildings. At first, its members met weekly to discuss architectural theory and practice as well as providing public lectures on architectural matters such as geometry, perspective and stone cutting but early in the eighteenth century these lectures had coalesced into a two or three-year course of study. By the end of the nineteenth century the Academy’s School of Architecture had developed a highly structured design methodology which was built around the atelier system with each student joining the office of a leading architect who also taught at the school.

Students were not required to attend lectures but instead, from their first day, were set design projects which were treated as competitions. As a ‘nouveax’‘ they would be given second-class building types to design – single houses, a small library or school – earning a ‘value’ or medal, when a jury of professional architects judged that their design proposal had reached an acceptable standard. They then progressed to the next stage of ‘ancien’, at which point they were set first-class building types to design, such as an opera house, palace or museum. Every project was expected to be developed in the language of Classicism and the study of the great books of Classical architecture such as Vignola’s ‘Five Orders of Architecture’, were essential to the development of an understanding of every aspect of the style.

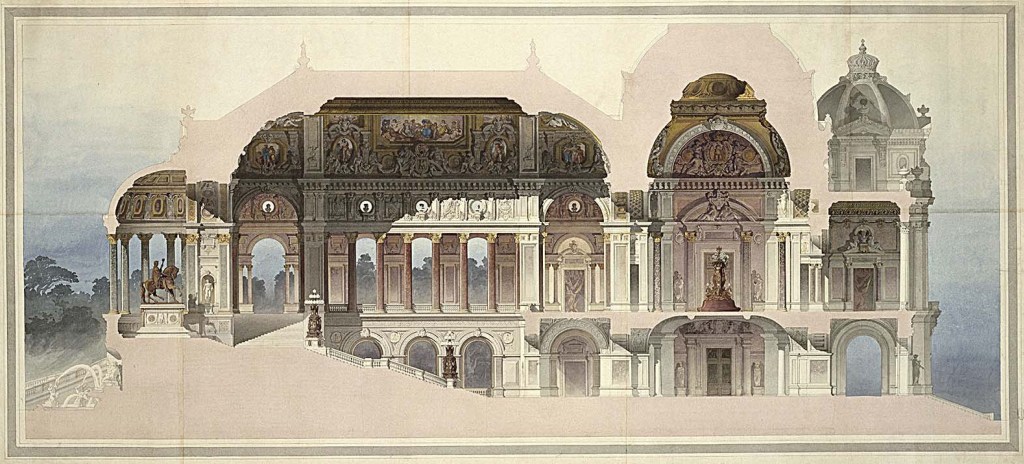

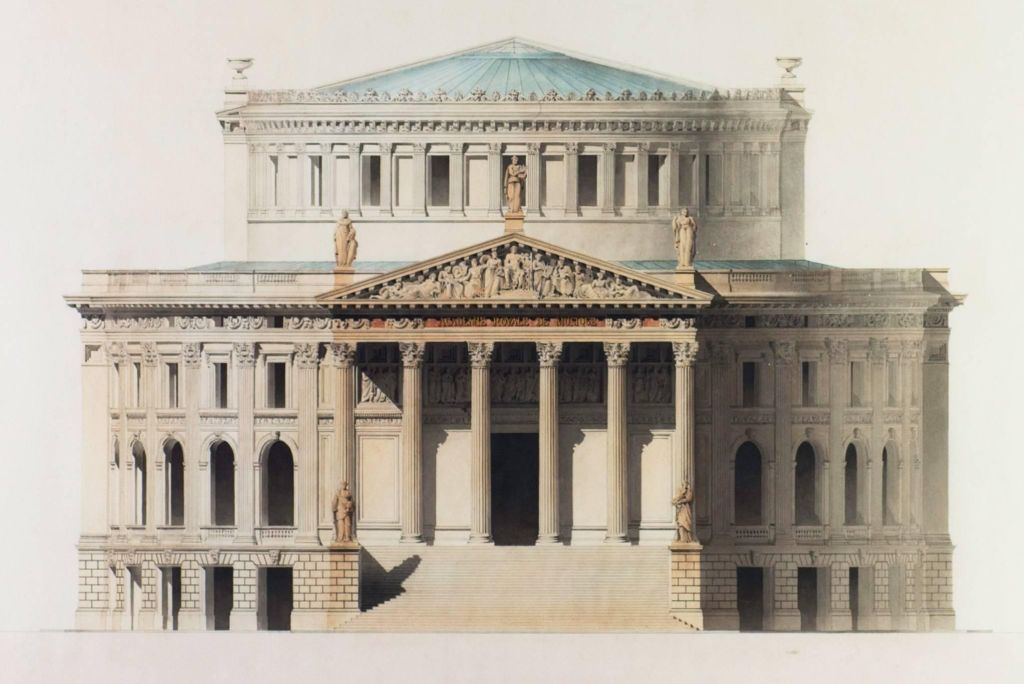

Even the method of developing a design was prescribed in detail, with students having to quickly produce a sketch or ‘esquise’, which must contain all the key elements of their proposed solution. Once their ‘esquise’ was accepted, an appropriate Classical order would be selected and the design further developed until it was presented as an ‘analytique’, which would be beautifully rendered in monochrome, before finally developing the design fully in plan, section and elevation, in a coloured ‘analytique rendu’. The standards expected were exceptional, and beautifully composed drawings with their immaculate draftsmanship and perfectly rendered shadows were required of all students if they were to receive medals for their work.

While principally a French school, it was also particularly popular with wealthy American students including Henry Hobson Richardson, Richard Morris Hunt, Charles McKim, Daniel Burnham and Louis Sullivan, for whom there was nothing comparable back home, and they imported the school’s neoclassical style to the United States where for many decades well into the twentieth century it was seen as the most appropriate style for all civic buildings and civic planning. Its proponents developed the style as an intrinsic part of the ‘City Beautiful’ movement which called for progressive social reform to counter the poor living conditions of many of the cities and as such (somewhat astonishingly from our twenty first century perspective) their Beaux Arts Neoclassicism represented a radical shift towards a new morality based on civic virtue.

If you don’t want to miss out on further blogs then please follow me on johngooldstewart.com