Continuing my deep dive into Victorian architecture for my latest book on architectural sculpture, I have been savouring the work of the extraordinary William Burges (1827-88). A committed Goth, he had neither the religious fervour of Scott, Butterfield or Street nor their success in winning architectural competitions. His career was languishing in the slow lane while he dabbled in jewellery, metalwork and stained glass until he was recommended as architect to John Patrick Crichton-Stuart, the 3rd Marquess of Bute in 1868.

Lord Bute was himself a fascinating character – a convert to Roman Catholicism and an admirer of all things Medieval – he preferred, like Burges, the architecture of the Age of Faith to that of the Age of Reason. Fortunately for Burges, he was also the richest man in the world at the time and the combination of his extraordinary wealth and Burges’ extraordinary imagination produced two buildings – Cardiff Castle and nearby Castell Coch (top) – in which they indulged their shared passion for the past in the creation of two fairy-tale retreats from industrial Britain.

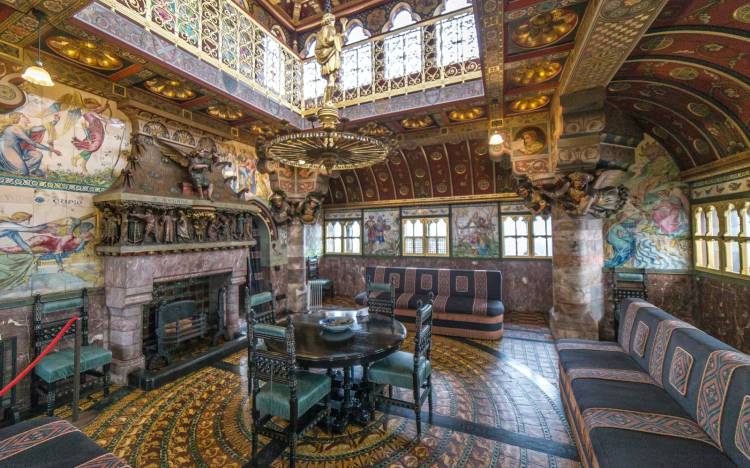

At Cardiff, Burges completely remodelled the existing accommodation within the castle as well as adding four towers, the tallest of which concluded in a double-height ‘Summer Smoking Room’ from which Lord Bute could look out to sea to the south and to the mountains of Wales to the north through an almost unbroken band of windows. One of the other towers provided a Guest Suite and within the existing accommodation he created an astonishing multi-vaulted Arab Room (largely inspired by his visit to Constantinople), a Chaucer Room, Nursery, Library, and Banqueting Hall, bedrooms for both Lord and Lady Bute and a vast new boundary wall topped with various animal sculptures. Castell Coch was completely restored from its ruined state and provided a similarly romantic summer lodge for Lord and Lady Bute.

Almost every surface of Burges’ interiors is decorated either in brightly coloured murals, painted or gilt sculpture, carved wooden panelling or mosaic tiling and every space within the castles is furnished with his original furniture in gilt and painted wood and lit by various wrought iron chandeliers of his own design. As Ruskin prescribed, there was little repetition amongst the details and only an artist with Burges’ apparently limitless creativity could have fully responded to this opportunity. But perhaps the most interesting aspect of his architecture is that, in contrast to much Victoriana, there is no hint of gloomy moralising or drippy sentimentality – every space, though often complex and rich, is fresh and invigorating.

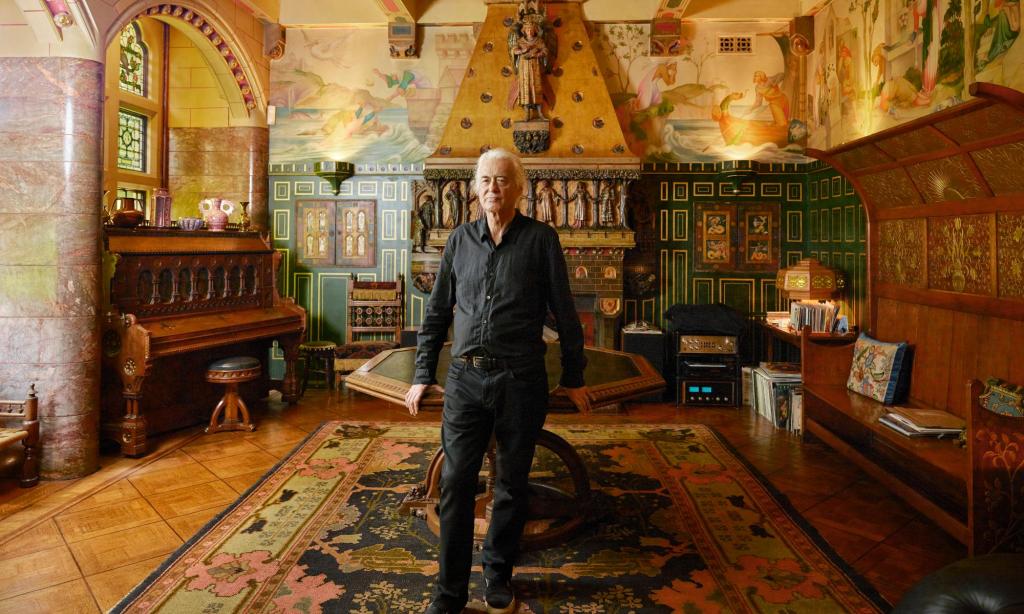

He later also designed and built his own house, The Tower House in Holland Park in London (1875-1881) which was described as “the most singular of London houses, even including the Soane Museum” and which fortunately, was superbly restored by Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page (before he moved on to Sir Edwin Lutyens’ Deanery Garden in Sonning, where he currently lives).

If you don’t want to miss out on further blogs then please follow me on johngooldstewart.com