There can be few artistic achievements in the entire history of mankind which top the architecture, sculpture and painting of Baroque Rome. At its height in Rome from around 1630–1680, Baroque is particularly associated with the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Its dynamic movement, bold realism (giving viewers the impression they were witnessing an actual event), and direct emotional appeal were ideally suited to proclaiming the reinvigorated spirit of the Catholic Church. The movement was dominated by one artist – Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) – the greatest sculptor and architect of his age.

His achievements were extraordinary, from the creation of St Peter’s Square to sculptures such as The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, his work set a new artistic standard and transformed numerous public spaces throughout the city. But for me, what made him utterly exceptional, was his ability to integrate sculpture with architecture to create a complete and seamless work of art in three dimensions. Though in many ways modest, his greatest architectural achievement is his small church of San Andrea al Quirinale, (1658-70) built for the Jesuit seminary on Quirinal Hill.

Like so many Roman churches, the exterior of the building is in a remarkably plain red brick and it is only the main entrance elevation which is in stone. This is set back slightly from the road to create a small space in front of the church which is enclosed by low quadrant walls and down into which the entrance steps cascade, setting up a certain dynamism between the concave and convex geometries. Below the pediment, a semi-circular porch steps forward and bears the coat of arms of Cardinal Camillo Francesco Maria Pamphili, Bernini’s patron on this occasion. In terms of Baroque Rome, this is an extremely restrained façade and is designed to lower expectations before entering the church.

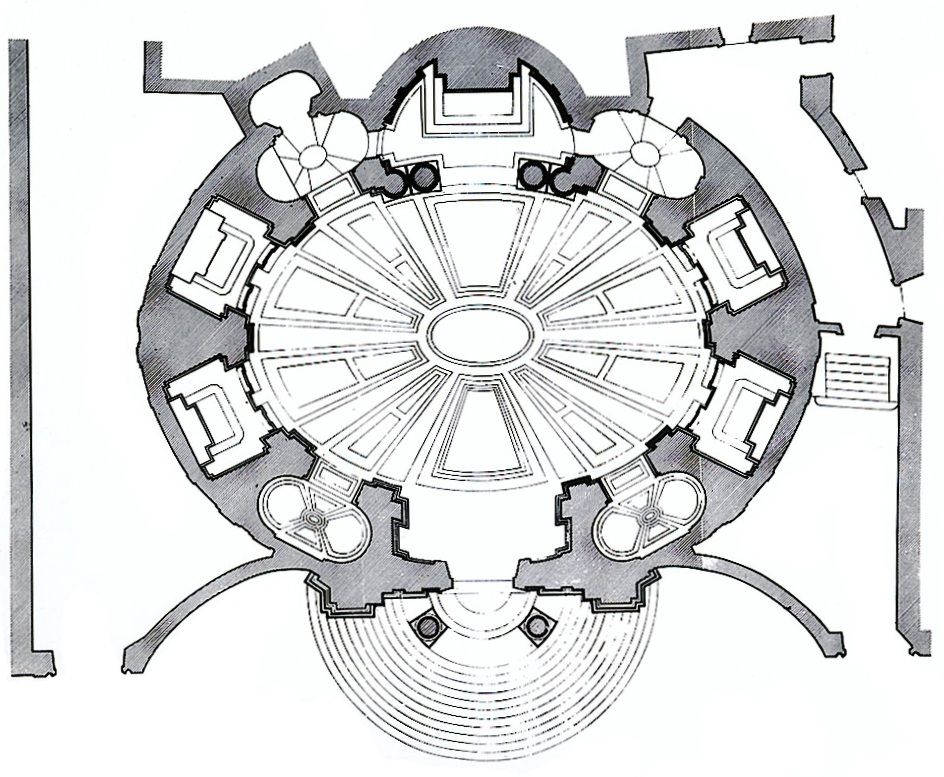

The plan of the church is oval, with the altar directly ahead almost overwhelming the visitor as soon as they enter. Borromini’s church, San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, which is just a little further down the same road, is also oval in plan but with the altar on the long axis, giving it a greater sense of tranquility but by, most unconventionally, turning the oval through 90o, Bernini has created a powerful feeling that the entire space is being squeezed, making the high altar almost overpowering and making the niche at its rear, which is lit from above, the inescapable focus of the entire composition.

Above the altar is a painting of The Martyrdom of Saint Andrew, which is surrounded by a host of sculpted angels within a golden sunburst, who draw the eye upwards towards the hidden light above, symbolising Saint Andrew’s ascension into heaven. This theme is then repeated by the sculpture within the broken pediment of the altar’s aedicule frame, who looks heavenwards to the light above the dome of the main space. The impact that this building still has on visitors after almost 400 years is almost overwhelming but just consider how it must have communicated the power and glory of God to a largely illiterate population back in the 17th century. Bernini considered it his greatest work and towards the end of his life often visited to enjoy what he must have realised was one of the greatest achievements of Western Art.

If you don’t want to miss out on further blogs then please follow me on johngooldstewart.com

Mastery of the elllipse, now that’s a talent ………

LikeLike