Richard Norman Shaw

I’ve written before about the brilliant Scottish architect Richard Norman Shaw (1831-1912). He dominated his profession in Britain in the final decades of the nineteenth century, developing what became known as the ‘Queen Anne’ style with his early partner William Nesfield before going on to lead the classical revival that would dominate the Edwardian age. His works are well known but his quite extraordinary draughtsmanship, much less so.

Like most of his contemporaries, his architectural education included several sketching tours of Europe and it was the drawings from his travels, which were published as ‘Architectural Sketches from the Continent’ in 1858, which first attracted attention to his exceptional abilities. While described as sketches, these were actually beautifully rendered views such as the tinted lithograph of the Tiergarten Tower in Nuremberg, which he included in the cover to his book.

While working in the office of George Edmund Street (1824-88), one of the leaders of the Gothic Revival, he continued to travel and sketch and also produced his own modest designs which again generated further interest when exhibited at the annual ‘Architectural Exhibition’ and later at the Royal Academy. After 16 years of study, training and practical experience, Shaw established his practice with Nesfield in 1863 and soon began to attract substantial domestic commissions, all of which were presented in beautifully rendered perspectives.

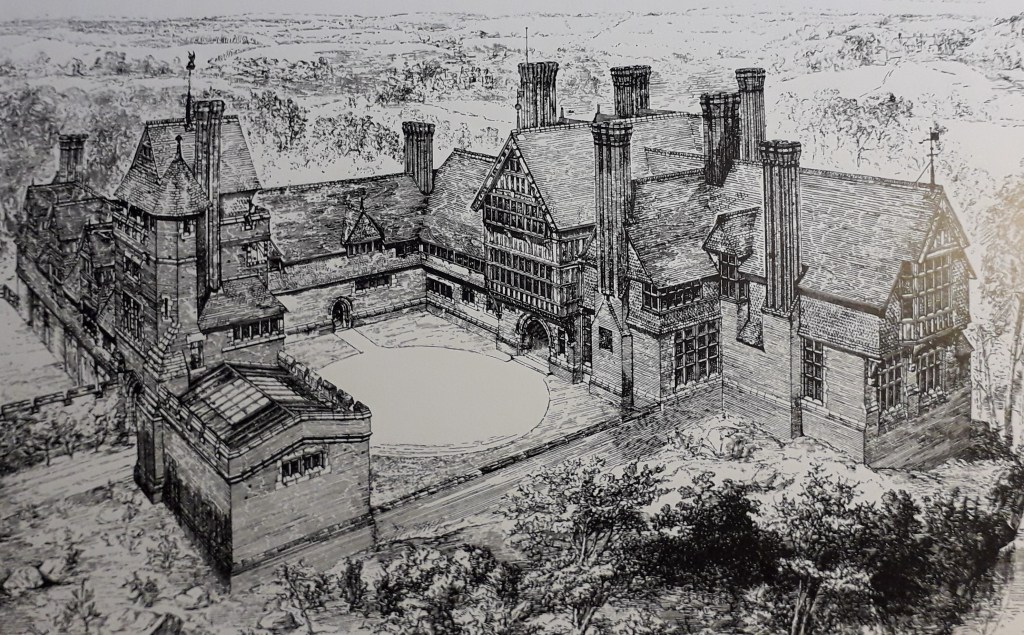

His perspective of Adcote of 1876-81, which he himself regarded as his finest house, is typical of these drawings, which convey not only the three-dimensional form of his proposals in extraordinary detail, but equally a sense of the place which he was in the process of creating. This drawing continues to be displayed in the Diploma Gallery of the Royal Academy to this day.

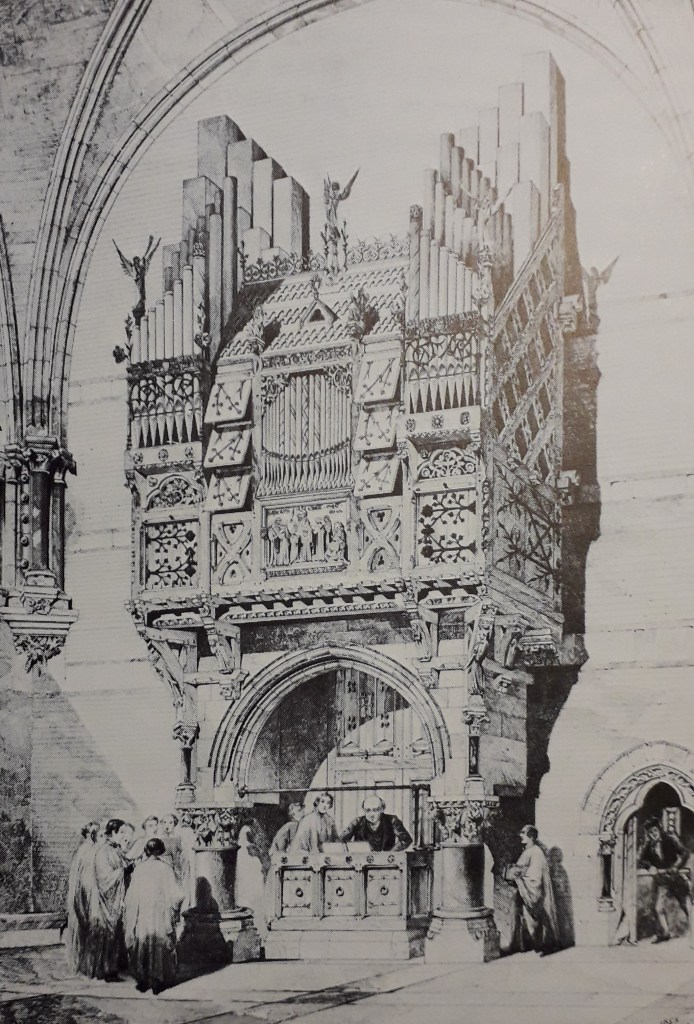

His extraordinary range and skills were also often applied to interiors such as in the early design for his church in Bingley in Yorkshire of 1864. There can be few finer architectural perspectives ever produced. As his practice became more and more successful, sadly, the production of perspective drawings was passed to his pupils with both Mervyn Macartney and Archibald Christie working within Shaw’s established style and producing similar work of a very high standard. To produce drawings as fine as these would be remarkable (not least as they were drawn with a pen dipped in ink) but when they also portray highly innovative architecture of an exceptional standard, we get to something approaching genius.

If you don’t want to miss out on further blogs then please follow me at johngooldstewart.com