New Delhi is often referred to these days in architectural circles as “Lutyens Delhi” but this does a huge disservice to Sir Herbert Baker who was responsible for the design of at least as many of the new city’s buildings as Lutyens. Lutyens and Baker were actually appointed as equal partners to both advise the Indian Government on all architectural matters relating to the new city and to design the principal buildings. In a fairer world, Baker might well have been appointed instead of Lutyens as he had already completed numerous public buildings including the South African government buildings in Pretoria (The Union Buildings) whereas Lutyens at this point in his career was very much still a country house architect; but Lutyens was based in London while Baker was in Johannesburg and his contacts proved crucial to his securing first the town planning and then his architectural role.

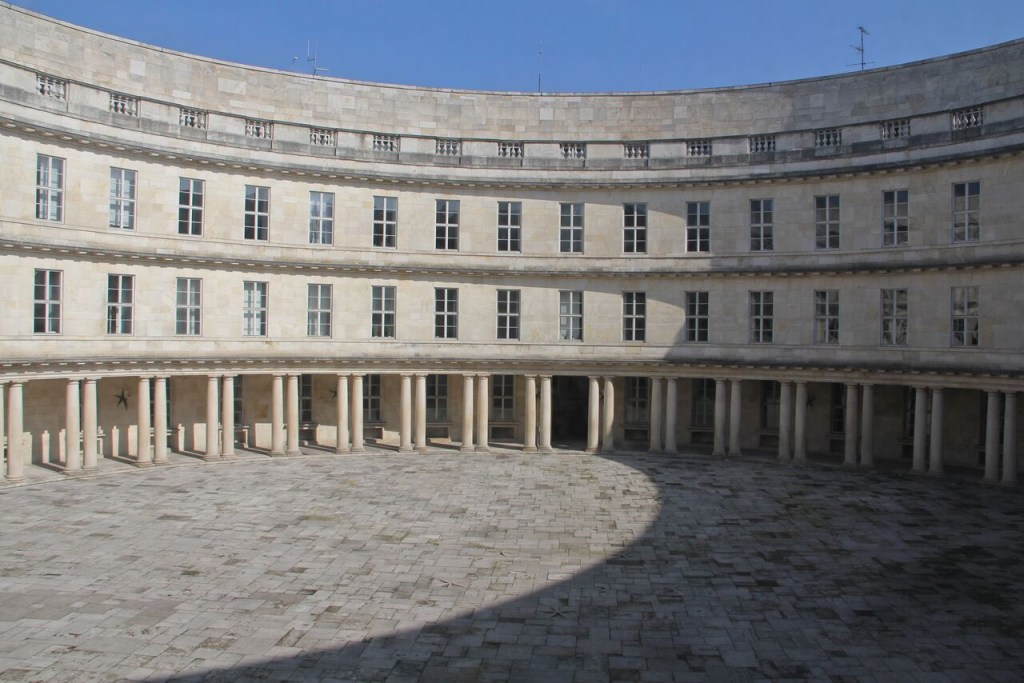

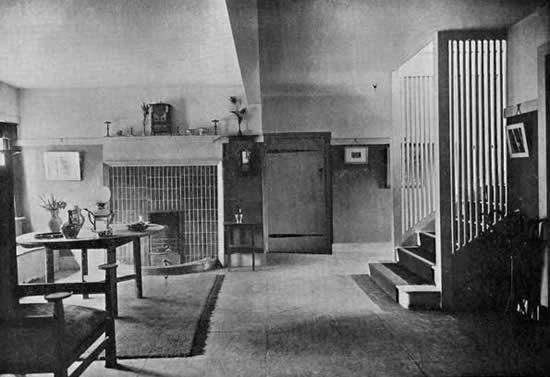

Amongst many other buildings, including the Indian Parliament, Baker designed the two Secretariat Buildings (above) to house the Indian Civil Service, which flank the processional way that leads to Lutyens’s Viceroy’s House. Each one is the size of the UK Houses of Parliament and while the interiors of Lutyens’s Viceroy’s House have been much published, Baker’s stunning interiors in the Secretariats are little known and now rarely seen by the public. The style of architecture used in New Delhi also owes more to Baker than Lutyens. When Baker arrived on the scene, Lutyens and the Viceroy were already locked in disagreement over an appropriate architectural style for the Imperial buildings with Lutyens favouring European Classicism while Hardinge the Viceroy, favoured Indo-Saracenic. It was Baker who, with a finely-judged letter to The Times, proposed the middle way that was used for all the New Delhi government buildings.

One of our most outstanding, least known and understood British architects, Baker’s life and work is covered in my latest book “Herbert Baker: Architect to the British Empire” which is due to be published by McFarland in 2021.